Venice, August 16, 2024. The blazing afternoon sun reflects off the boats gliding taut along the canals, making the still waters of the lagoon boil; it glances off the iron prows of the black gondolas; it strikes mercilessly the crowds huddled on the vaporetto.

Venice in August always holds something of the fairy-tale, an atmosphere reminiscent of “One Thousand and One Nights,” so distant from the cold climate of its shocking red December.

In these brackish waters, where everything reflects and distorts, lies the mystery of Titizé, the new show by the Finzi Pasca Company, hidden from sight like the Clavicula Salomonis.

The Goldoni Theatre, a seventeenth-century Venetian jewel, is filled with the chirping of cicadas; the backdrop on the stage is blue streaked with white. Behind me, a young boy asks his father if it is the sea or the sky, but there is no answer to this question. Then the chirping intensifies, as if the cicadas wanted to hush the chatter of the audience; the lights slowly dim to darkness, and the Venetian dreams of Titizé unfold before the spectators’ eyes.

These are vivid, coherent, and finely crafted dreams; do not think of a nonsensical dream world where the unconscious shatters and distorts reality. The dreams of Titizé are rather revelations, opening glimpses of understanding into the world.

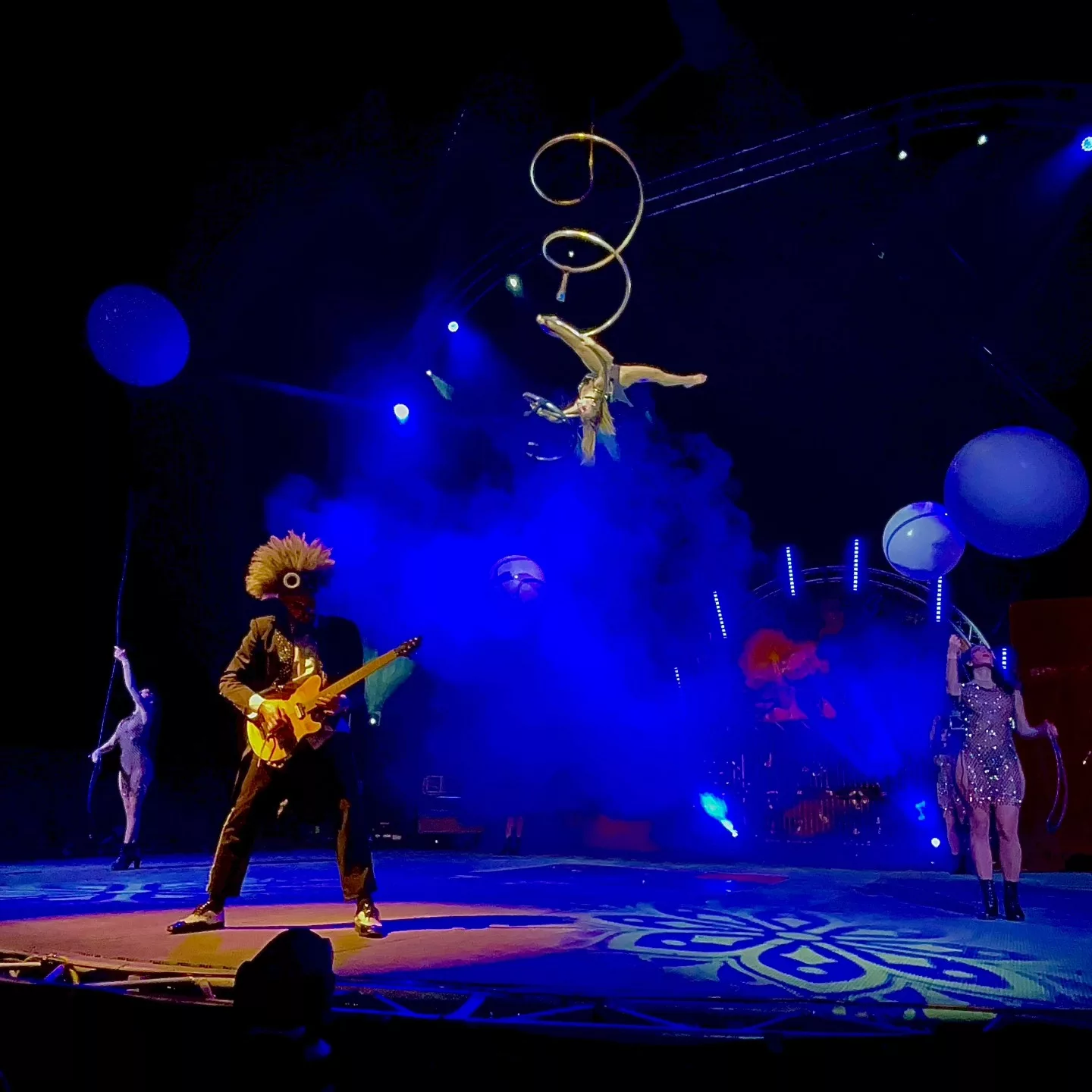

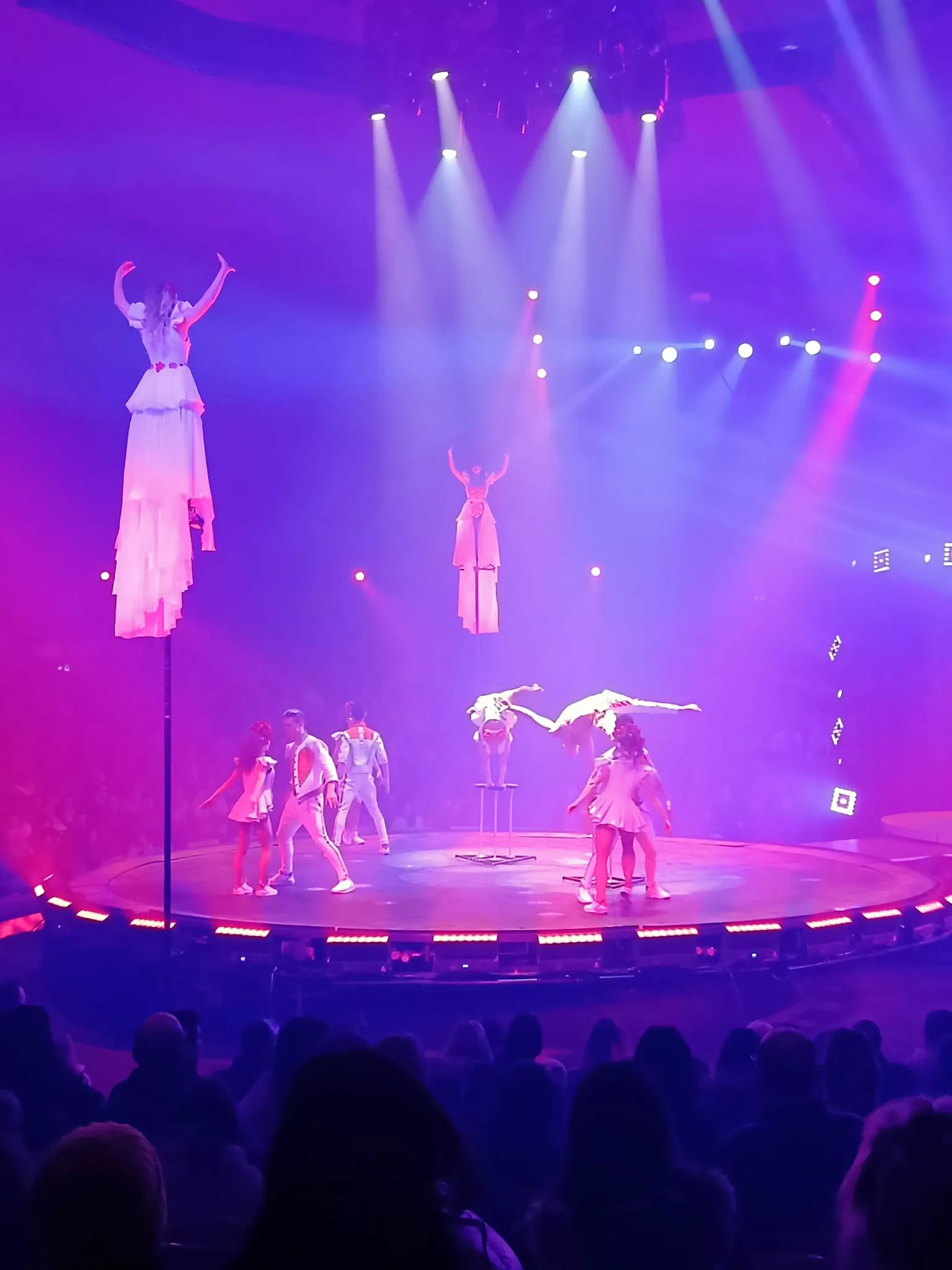

Titizé is a grand circus show, although this term does not appear in its presentation. In fact, more precisely, it is a performance where the circus is subservient to a broader and bolder artistic enterprise, where it becomes merely a tool, an artifice suited to creating a sense of wonder. Illusionism is also used for the same purpose, presented in a comic and farcical key. On closer inspection, all artistic elements are consistently dedicated to the common endeavor masterfully orchestrated by Daniele Finzi Pasca, without any overwhelming components. The thematic scenes are perfect in their rarefied light, propelled by the music of Maria Bonzanigo, and live with acrobatic dynamism and grotesque masks that hide all-too-human faces.

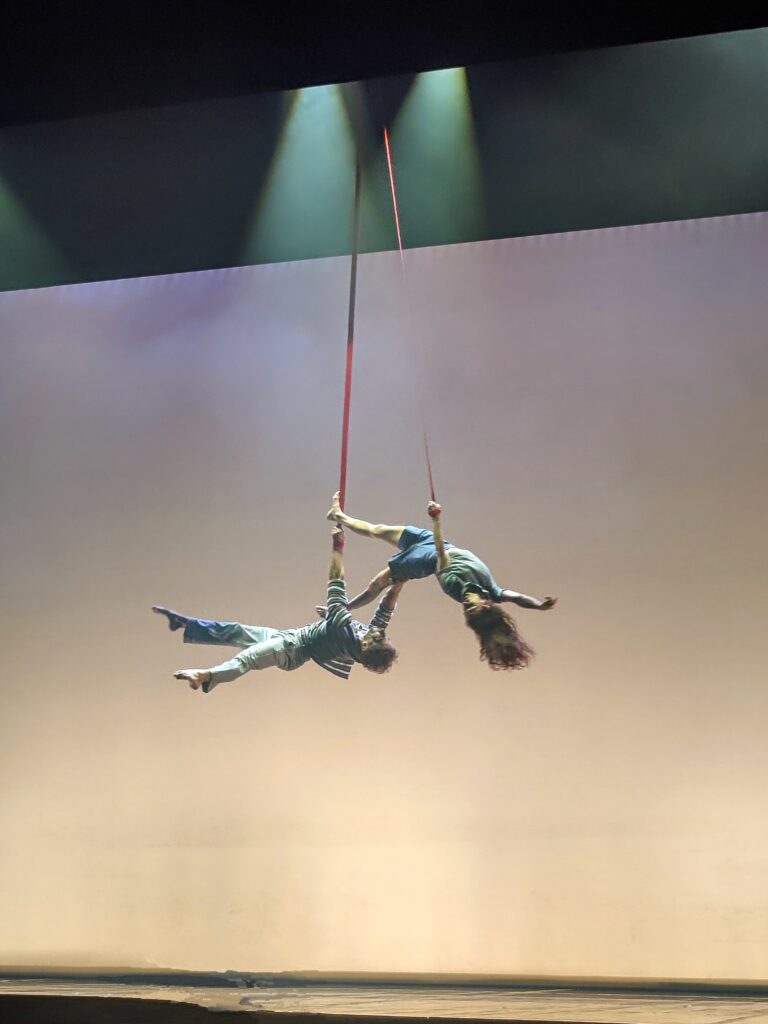

The mask is indeed one of the central elements of the work. The actors and acrobats often appear masked, as if they were participating in the ancient Venetian carnival; in stark contrast, some performances, such as the Chinese pole or the aerial straps number, are carried out by acrobats in ordinary clothes, as if they were mere tourists who, during a vacation, find themselves immersed in the fantastic reality of Titizé, this word that vaguely sounds like “you are” in Venetian. And the audience feels this closeness, almost sensing they are spying on fragments of lagoon life. They find themselves peeking at the rendezvous taking place on the rue cyr between a vigorous and whirling man and a woman blinded by love, who performs with a blindfold. They glimpse a heroic and warlike, farcical past, where a mighty armor flies through the air as if lifted by the strings of a gigantic puppeteer, only to fall back to the ground, at the mercy of events. They observe the life of the Lido, where a diver swims in the sky, as if the beach where the bathers sit were at the bottom of the sea, and where even a mermaid with a long scaly tail appears.

There is always a playful, irreverent component, sometimes even a deliberate revealing of the stage fiction, which is just one of the many masks of reality.

The spectator watches these different scenes alternate, but they are united by a constant presence: Venice. The saline and oriental scent of the city permeates the air of the show; everything is played out in the mental labyrinth of its narrow streets. When the actors speak, they use Venetian, occasionally slipping into English, as if addressing tourists from distant lands. Everything aims to tell the story of a lived-in Venice with many masks, and for this very reason, the spectator ends up feeling part of the narrative cosmos.

Leaving Venice, watching the wake of the vaporetto in the now dark waters of the evening, one is left at the mercy of this mystery. Titizé tells something that you, too, are—a pilgrim who has come seeking something in the waters of the lagoon, among the streets of Venice: perhaps only beauty, perhaps a face behind the mask.